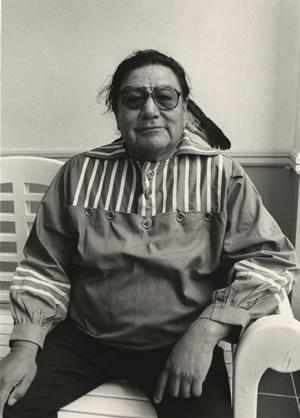

Gerald One Feather

The great Lakota chief, Sitting Bull, once noted, “when I was a boy, the Sioux owned the world. The sun rose and set on their land; they sent ten thousand men to battle. Where are the warriors today? Who slew them? Where are our lands? Who owns them?” Gerald One Feather has dedicated his life to the recovery of the spirit, land, and cultural inheritance of his people, working within the tribal government of the Oglala Sioux and outside it.

Gerald One Feather grew up on the Oglala Sioux Reservation in Pine Ridge, South Dakota, in the poorest county in the United States. He was one of seven children and the grandson of tribal medicine men who guided him to take public responsibility. Gerald attended the Pine Ridge Indian boarding school, which he maintains gave him a decent education and ultimately influenced his belief in the potential of public education. He went on to earn a B.A. and become a candidate for a Master’s in political science from the University of South Dakota and the University of Oklahoma.

Combining his practical and academic knowledge of political processes and traditional Native American government (he had studied the Osage tribe’s two-party system as a graduate student), he returned to Pine Ridge to put his skills to work for his people. In 1963, after a short time in the accounting office of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Gerald was invited by the Tribal Chair of the Oglala Sioux to work on mobilizing the tribe against proposed legislation that would give the state jurisdiction over all criminal proceedings on the reservation. Gerald agreed to become Secretary of the tribe, but the office of Vice President was vacant and on his first day in office, Gerald was promoted to that post on an acting basis.

As a member of the tribal government, Gerald instituted several programs that later became national models. During the 1960’s, he helped a community health representative who paired Lakota families with health care workers. Gerald is now responsible for a model co-op housing plan authorized by the tribe in 1998, which accommodates the tiospaye, the traditional extended Lakota family living arrangement.

Despite the resistance of the state of South Dakota, Gerald forged the way for the creation of the Oglala Lakota College on the reservation to provide job training for police officers, probation officers, health care workers, and teachers. Bypassing the South Dakota Board of Regents, which refused to help, Gerald enlisted the support of the University of Colorado to establish a model for American Indian education. This model has been replicated to create 26 such colleges on reservations around the country.

Gerald has been involved in the United Nations’ work on indigenous rights and in the effort to restore the strength and independence of The Great Lakota Nation—the many bands, or subgroups of the Lakota, that are now considered separate tribes by American and Canadian Indian Law. Gerald has been an important force in reexamining treaties and bringing together leaders of both Canadian and American tribes in annual summits to reestablish the Campfires, the traditional Lakota government. “My vision is to see the Lakota people control their own lands and revive their culture, ceremonies, and traditions.”

Gerald One Feather has revitalized and strengthened many Lakota families through economic self-sufficiency and cultural preservation. The father of seven children and four stepchildren, Gerald is committed to the traditional extended Lakota family, the tiospaye. He and his wife are currently trying to bring back the traditional Lakota coming-of-age ceremonies and oversee the tribal initiation of a growing number of Lakota boys and girls each year. “We put boys on a vision quest to develop a relationship with the spirit in their bodies and the spirit in the universe,” Gerald says. “Young people are our future. What we teach them today they’ll be practicing ten or fifteen years down the road.”

Photo by Dorothea von Haeften

Photo by Dorothea von Haeften