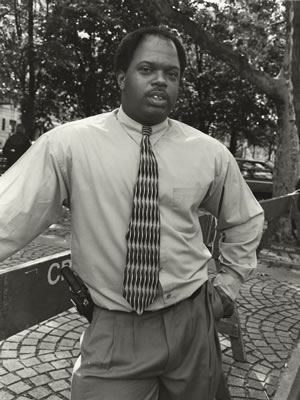

James Gilmore

James Gilmore is a New York City police detective who has taken a courageous stand against racism within the police department and against police brutality. He does more than work to protect his precinct’s residents from crime; he encourages them to demand a just and responsive system of law enforcement and to take responsibility for their own community’s well-being. He embodies our best hopes for police officers and reminds us that restoring law and order is impossible without securing social justice.

James’s father, Irving Gilmore, was also a police officer. In 1964, working undercover as a detective in Harlem at a time of great racial tension, James’ father got a tip late one night that two white policemen would be shot in retaliation for a police shooting of a black teenager.

Heading outside to sound the warning, Irving Gilmore bumped into a young, white colleague and urged him to get off the street to safety. As they spoke, the pair was joined by a group of white uniformed officers. As he was pulling his shield out of his boot to identify himself and passing on his urgent news, Irving Gilmore was called a “black bastard” by one of the officers and struck in the head with his nightstick. Protecting himself, as another officer attacked, Irving Gilmore was forced into a police wagon and driven to the station house, where he was recognized and taken for medical attention.

Hospitalized for many months, Irving Gilmore never returned to the police department and he continues to suffer neurological problems as a result of the attack.

His son, James, graduated college with a degree in political science and hoped to go to law school. Finding it difficult to secure a decent, well-paying job, James reluctantly took the civil service exam and joined the NYPD.

Assigned in 1987 to a pilot community policing program in the upper Manhattan neighborhood of Sugar Hill—dubbed in the precinct, “the belly of the beast”—James was determined to treat the people on his beat as individuals with “dreams and aspirations” rather than as “objects of potential police action.”

James got to know the neighborhood residents well enough to distinguish hardened criminals from innocent bystanders caught in a police sweep. Despite repeated death threats and a bomb planted in his home that injured his niece, James doggedly pursued dangerous drug gangs. He has earned a dozen citations for his work, including one from the New York Police Department’s Organized Crime Unit, and has received his detective badge.

In addition to his police work, James has contributed his time and resources to the community. He has taken young people on country outings and weekend retreats, checked their report cards, and helped them solve school and family problems. He has advised tenants fighting landlords who violate the law, helped maintain a safe passage program for seniors, and guided addicts into drug rehabilitation programs.

In 1997, James co-founded 100 Blacks in Law Enforcement, a fraternal organization, to expand the numbers of law officers working for social justice. Besides assisting victims of police brutality and others in need, members speak to school, church, and local gatherings about effective responses to police encounters.

As James continued to challenge police practices and procedures, his status within the precinct changed and in February of 1997 he was abruptly reassigned to the Bronx.

Two months later, after a massive community outcry on his behalf, the NYPD returned James to the 33rd precinct but assigned him to a position that limited his access to the community. James was back in the neighborhood just in time to receive a frantic middle-of-the-night call informing him of the fatal police shooting of Kevin Cedeno, a 16-year-old he knew well. He joined the family in mourning and advised them to seek an independent autopsy. The autopsy contradicted official descriptions and indicated that Kevin had been shot in the back.

In the face of harassment, hostility, and disciplinary action, James Gilmore continues his work within the community, guiding adolescents to assume the responsibilities of adulthood and organizing the neighborhood to improve itself, building by building, block by block.

Photo by Dorothea von Haeften

Photo by Dorothea von Haeften