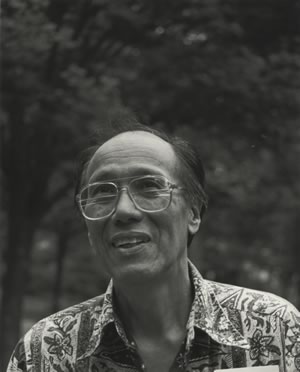

Kekuni Blaisdell

When the first colonizers landed on the Ka Pae ‘Aina (the Hawaiian Archipelago) in 1778, they were greeted by a people who introduced themselves as the Kanaka Maoli—Kanaka meaning “human being,” Maoli meaning “real” or “genuine.” But to the colonizers they were “naked savages.” Almost immediately the process of stripping the “real” people of their land, resources, and culture began. Kekuni Blaisdell, a Kanaka Maoli from the island of O’ahu, has spent his life promoting the spiritual and physical health of the Kanaka Maoli and restoring their nation.

“My toes and feet are deep in our mud,” Kekuni says of his heritage, “My roots are strong here.” As a boy, he was sent to the Kemehemeha boarding school for Kanaka Maoli on the island of O’ahu, to be trained to be an electrician. “The policy of the school was to bleach us—to make us blue collar workers for the plantations. Our language was banned, all the teachers were white,” he says. However, one teacher took an interest in Kekuni, and urged him to go away to college—something almost unheard of at the time for a Kanaka Maoli youth. Kekuni’s working mother raised enough money to send him to the University of Redlands in California. When World War II began, he was able to get a deferment to go to medical school at the University of Chicago.

At the beginning of the Korean War, in the middle of Kekuni’s residency in medicine, he joined the United States Army as a medic. He was sent to East Asia—first to the hills of Korea as a battalion surgeon, then to Japan and to Taiwan where he trained Chinese Nationalist army doctors. After completing a medical residency and hematology fellowship, Kekuni returned to Japan as the Chief of Hematology at the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, where he spent two years examining bomb victims and documenting the horrors of the nuclear holocaust. While in Japan, Kekuni adopted his Japanese son.

In 1966, he returned to Honolulu with his wife, also a Pacific Islander, and his daughter and son, to become the first Chair of Medicine at the University of Hawai’i. Kekuni prepared a comprehensive report on the health of the Kanaka Maoli, documenting that they suffer from the highest rates of heart disease, cancer, infant mortality, stroke, diabetes, teen-age pregnancy and complications and had the shortest life expectancy of all the ethnic groups in Hawai’i. The Kanaka Maoli also have the highest rates of school drop-outs and incarceration, and the lowest level of income and home-ownership in the Islands. Kekuni sought to address these problems as a whole, and began integrating traditional holistic medicine into his practice and reinforcing cultural identity. “When I was a youngster,” he says, “the term Kanaka was one of derision—it meant stupid, worthless. . .We must reclaim it to identify with our ancestors and find strength in the connection with our sacred environment, which embodies them.”

As Kekuni examines the overall pattern of Kanaka Maoli suffering, he turns to the source of the cultural identity crisis: Kanaka Maoli sovereignty. “The basic concept of our colonizers is to exploit us—to use our natural resources and people for individual gain,” he says, “but capitalism is the antithesis of the Kanaka Maoli tradition. . .[which] holds that we must be in harmony with all the forces about us and share.” Kekuni sees Kanaka Maoli independence as the only way to Kanaka Maoli survival.

Kekuni seeks to raise the awareness of both the local Kanaka Maoli and the world community of the disenfranchisement of the Kanaka Maoli. In 1993, he convened an international tribunal of renowned legal and human rights experts, who found the U.S. government guilty on nine charges of human rights abuses and unlawful occupation. Kekuni has prepared a petition to the United Nations and the United States to recognize the illegal colonization of the Ka Pae ‘Aina and to begin the process of de-colonization.

“The U.S. Congress has projected that in the year 2044 there will be no more pure-blooded Kanaka Maoli and therefore we will be proclaimed extinct, so there is urgency to the situation,” Kekuni says. He supports land struggles in which families return to living off the land. Half of the Ka Pae ‘Aina is held in trust by the state of Hawai’i, which has failed to meet even the most basic needs of the Kanaka Maoli people.

Kekuni has chosen a difficult road to cultural and political restoration of the Kanaka Maoli. He is often at odds not just with the state and federal government, but with other Kanaka Maoli groups who are willing to settle with the establishment in return for specific concessions. For the last two years, he has fought an uphill battle against a state plebiscite for a state controlled Native Hawaiian Constitutional Convention instead of a true Kanaka Maoli self-determination process.

Kekuni Blaisdell sees the struggle for independence as lifelong. He draws strength from his ancestors and is encouraged by the support of his daughter and son and his four young grandchildren who, he says, “are beginning to learn what it means to be Kanaka Maoli.”

Photo by Dorothea von Haeften

Photo by Dorothea von Haeften