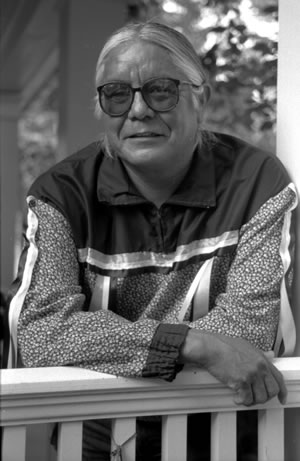

Lenny Foster

In May of 1972, a group of spiritual leaders involved in the American Indian Movement (AIM) went to Minnesota’s Stillwater prison to perform a traditional Native American Pipe Ceremony. For 23-year-old Lenny Foster, one of the youngest AIM participants, this powerful experience would set the direction for his life’s work. “It had a profound impact on me,” he says. “I could see the hope on [the prisoners’] faces. I felt so good that I could pray in my native tongue. That was fate. Destiny.” Recognizing the importance of traditional Native American religious practice as a source of strength and a necessary means of cultural preservation, Lenny has spent the last 28 years fighting to ensure that incarcerated Native Americans have the right to worship with access to their traditional ceremonies.

Lenny grew up in Fort Defiance, Arizona, with his mother and his father, a Navajo code talker during World War II. Lenny attended an Indian school as a day student and lived with his grandparents on a traditional Navajo sheep camp over the summers. “This traditional upbringing serves as a foundation of who I am today,” he says. “I’ve made it my calling to go to institutions where Native Americans are incarcerated and share it with those who didn’t have the opportunity to learn the traditions and to draw strength from their spiritual heritage.”

After trying out unsuccessfully for the Los Angeles Dodgers’ farm team, Lenny went to Arizona Western Junior College and then to Colorado State University. In college, he had his first exposure to the civil rights movement. “People were talking about riots in Detroit and Malcolm X and Martin Luther King,” Lenny says, “and I was wondering—where do I fit in?” Lenny joined the American Indian Movement.

In 1970, he was involved in the occupation of Alcatraz and, in 1972, in the Trail of Broken Treaties Caravan and the Bureau of Indian Affairs take-over in Washington, D.C. He took part in the 71-day protest at Wounded Knee in 1973. In 1978, he participated in the Longest Walk, a seven-month journey from Alcatraz to Washington, D.C., to protest proposed legislation that would eliminate the federal government’s fiduciary responsibilities to American Indian nations.

In 1981, as a graduate student in public administration, Lenny volunteered in the Arizona State prisons, where he constructed the first prison sweat lodge in the Southwest. Eventually he realized that his heart lay in this work, and he left his graduate program to pursue it full time. In 1983, the Navajo Nation tribal government began to support his efforts to provide spiritual counsel to incarcerated Native Americans. Today, as the Spiritual Advisor and Director of the Navajo Nations Corrections Project, he is responsible for the traditional spiritual guidance of 1500 inmates in 89 state and federal penitentiaries. “Many prison administrators don’t want Indian people to succeed. They are threatened by the return to spiritual beliefs and want to deny Indians the right to rehabilitate themselves through spirituality,” he says. He is troubled by the high rate of suicide among Native American prisoners, especially juveniles. “We’ve been made to feel ashamed—our long hair has been cut, our sweat lodges have been bulldozed, our eagle feathers have been broken—this results in so much pain and anger.”

Lenny draws strength from the growing support of the outside world for his cause. “I was overwhelmed to hear that Petra Shattuck, a German-American from the East Coast, was working for American Indian rights. I can say this much better in Dine,” he says, “but to be, through her life, drawn into a warrior society that believes in peace and dignity—for the red nations to join in this arena and share this solidarity means a great deal to me.”

Lenny has authored and co-authored legislation protecting the rights of incarcerated Native Americans in four states in the Southwest. He has testified before the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs on several occasions. He has been a board member of the International Indian Treaty Council since 1992. In January, 1998, Lenny’s testimony on the overlooked rights of American Indian prisoners was accepted by the United Nations Human Rights Commission. Later that same month, the Association of State Correctional Administrators accepted his proposal to develop standards for American Indian religious freedom within all correctional facilities.

A member of the Grand Council of AIM since 1992, a member of the Native American Church and an active Sundancer, Lenny is active in the protest of the forced relocation of the Dine people in Big Mountain, Arizona.

Lenny Foster is concerned that today’s American Indian youth are less exposed to the traditions that gave him strength. “The responsibility we have as Indian people to teach our children and youths is great—alcoholism, drugs, broken homes are everywhere—you don’t have the role models my generation had.” By offering those most in need of support the kind of spiritual guidance he had as a boy, Lenny Foster shoulders his responsibility to pass on tradition and, in so doing, to pass on strength.

Photo by Dorothea von Haeften

Photo by Dorothea von Haeften