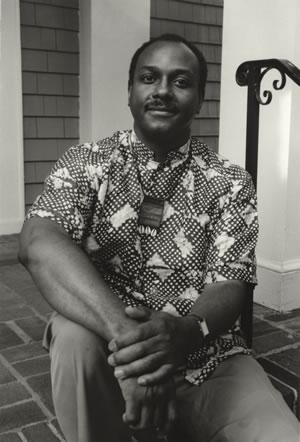

Samuel Cotton

Most Americans believe slavery disappeared over 130 years ago. In 1995, Samuel Cotton organized the International Conference on Chattel Slavery and founded CASMAS, the Coalition Against Slavery in Mauritania and Sudan, dedicated to raising the awareness of the American public about contemporary slavery and human rights abuses in Sudan and Mauritania. He has traveled undercover in the heart of present-day slavery, presented his research to Congress (before the Subcommittee on International Operations and Human Rights), and has written a book about his abolitionist work. His ethnographic research about slavery in Mauritania, captured on film, was acquired by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Despite intense opposition, anger, and physical threats, Samuel combines activism with academic thought and national and international advocacy, through the spoken and written word, to communicate the shockingly unknown story of present-day slavery. He was raised in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, and has a M.A. degree in social research. He is currently a Ph.D. candidate in social policy at Columbia University, where he also teaches social policy. While a student, Samuel worked as an investigative journalist for the Daily Challenge, the New York Post, and Vibe Magazine.

In 1995, the City Sun, an African-American newspaper, hired Samuel to investigate allegations of contemporary enslavement of black Africans in Mauritania and Sudan. Samuel’s conclusion was startling: chattel slavery of black Africans is still an entrenched problem in some African countries. He found that race was the determining factor in slavery, and that dark-skinned Muslims and black Christians are being held in bondage by lighter-skinned Muslims. Samuel found people willing to risk their lives in Africa to carry out strategies for resistance. He went undercover for 28 days to interview leaders of anti-slavery operations in Mauritania, as well as slaves and runaway slaves. In Mauritania alone, he estimates, there are 90,000 slaves, but the government suppresses all information and punishes any form of resistance. He explains, “I felt guilty doing the interviews because I knew I could get them (anti-slavery leaders) in trouble. But they kept telling me: ‘Our job is to die for this.'” Anti-slavery workers in Mauritania are often tortured, and are sent to prison. Sometimes they disappear.

As Executive Director of CASMAS, Samuel is creating a “Freedmen’s Bureau” to educate, feed, clothe, and house slaves in Mauritania as they make their way toward freedom. Samuel has received very little outside financial help and shoulders most of the costs of his work. Almost daily he receives faxes and letters soliciting help and solutions from anti-slavery leaders and slaves in Mauritania.

Since founding CASMAS, Samuel has often encountered both apathy and hostility. “This is a study in talking to walls,” he explains. “African slaves have no advocates. There is a public, political, and spiritual indifference.” Samuel has appeared in a series of radio and television debates with the Nation of Islam. He has been called a “puppet of the Jew” and been accused of writing propaganda intended to “divide an already divided African-American community.” He explains, “I’m not against Arabs or Muslims, I’m for exposing the truth.” Samuel accepts the responsibility to battle the ignorance of enslavement and the hostility toward abolitionists. To counter the indifference, he has written articles, held meetings at universities and churches, and traveled throughout the U.S. speaking in public forums.

Samuel often asks himself if anything has changed since the times of Frederick Douglas. “My people are still being enslaved, and it is humiliating. This is a psychological and spiritual war,” he says. “People think what I do is interesting and exciting. No, it’s disgusting. It’s depressing. Sometimes you wish you weren’t involved. It’s a terrible feeling.”

In August, 1998, Harlem River Press published Silent Terror: An African-American‘s Journey into Slavery, which chronicles Samuel’s abolitionist activity in the U.S. and in Mauritania. For most writers, publishing a book is a celebratory experience, but Samuel feels he is ‘wearing a red suit and walking into a bullring.’ He is concerned that the testimonies in the book will only exacerbate the vehement objections of his critics.

Samuel Cotton’s credo captures his struggle: “The key to preserving your humanity in the face of oppression is resistance. And it’s resistance whether you win or not. If you don’t accept it, you lose your humanity.”

Photo by Dorothea von Haeften

Photo by Dorothea von Haeften